After weaning, a female calf becomes a heifer, which will eventually replace the culled animals, increase the herd size or be sold to generate income. After weaning, heifers should be grouped according to size in small, uniform groups that have adequate access to forage and concentrate. Balance the ration and consider feeding a total mixed ration. Heifers should be closely observed and fed correctly to avoid the growth slump that can occur after milk is withdrawn.

1. Aim of heifer feeding

Heifers should achieve a growth rate of 500–700 g/day. This ensures that they will come on heat at the right time, as puberty is related to size rather than age. Reduce the interval between weaning and first calving to increase the number of calvings per lifetime (more lactations) and lead to faster genetic improvement. Achieving first calving at 27 or fewer months of age is possible only if the growth rate is high.

2. Feeding

On most farms, heifers are normally the most neglected group in terms of feeding, resulting in delayed first calving. When heifers of different ages are fed as a group, aggressiveness varies such that when concentrate is fed to the group, some get little. Heifers should thus be reared in groups of similar age or size—weaners, yearlings, bulling heifers (those that are ready for breeding) and in-calf heifers.

Heifers can be reared on good-quality pasture as their nutrient requirements are low (growth and maintenance). Supplementation with concentrate should be at 1% of body weight with 12–14% crude protein for heifers on legume forage and 15–16% crude protein on grass forage.

Protein is extremely important in the diet of growing heifers to ensure adequate frame size, wither height and growth. Avoid short heifers by balancing the ration and including enough crude protein.

While designing heifer feeding programs, it is important to consider the following:

- Puberty, which is related to calving age, is also related to size (a feeding indicator) rather than the age of the heifer. The consequences of poor feeding are therefore manifested in delayed first calving and commencement of milk production.

- Feeding heifers too much energy leads to fat infiltrating the mammary glands, inhibiting development of secretory tissue, thus reducing milk yield.

- Underfeeding results in small-bodied heifers, which experience difficulty during calving (dystocia).

• The size of the animal is related to milk yield. With twins of the same genetic makeup, every kilogram advantage in weight one has over the other results in extra milk.

- Overfeeding heifers on feed high in energy but low in protein results in short, fat heifers; high protein and low energy feed results in tall, thin heifers.

Underfed, hence slow-growing heifers may reach puberty and ovulate but signs of heat may be masked (silent heat), while those in good condition will show signs of heat and have higher conception rates. Over-conditioned or fat heifers have been reported to require more services per conception than heifers of normal size and weight.

3. Growth rate (weight and height) vs age

To monitor the performance of heifers, measure the body weight and the height at withers and plot on a chart. Growth of the heifer should be such that any increase in weight should be accompanied by a proportionate change in height.

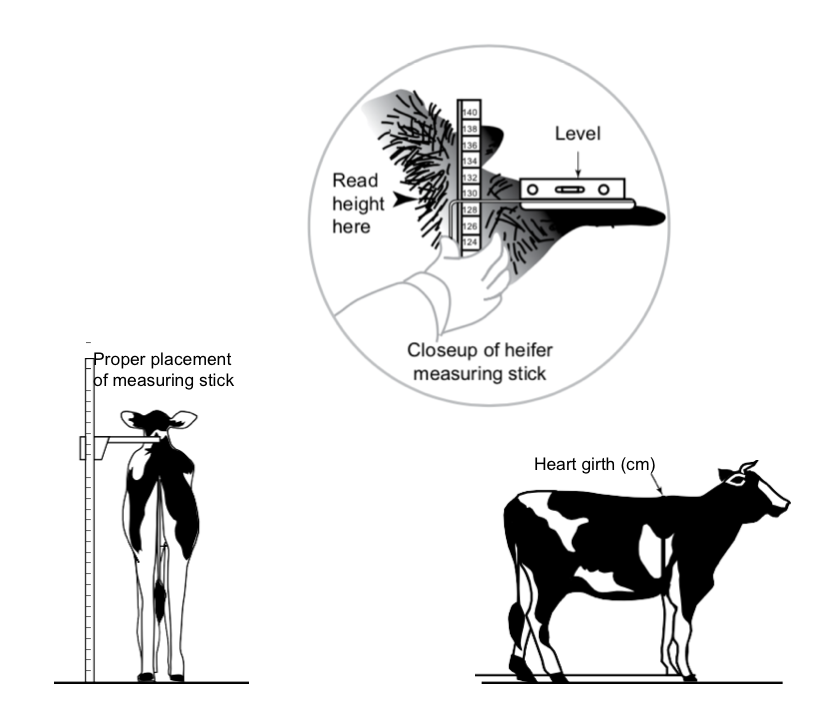

Standard charts have been developed for different breeds with the expected weight and height at different ages for different breeds. Where weighing facilities are unavailable, the weight may be estimated based on the heart girth in centimetres. Measure the heart girth using a tape measure and use a weight conversion table (see Appendix 3) to get an estimate of the weight based on the heart girth. The height can be measured by a graduated piece of timber as shown in Figure 7.1.

Heart girth (cm)

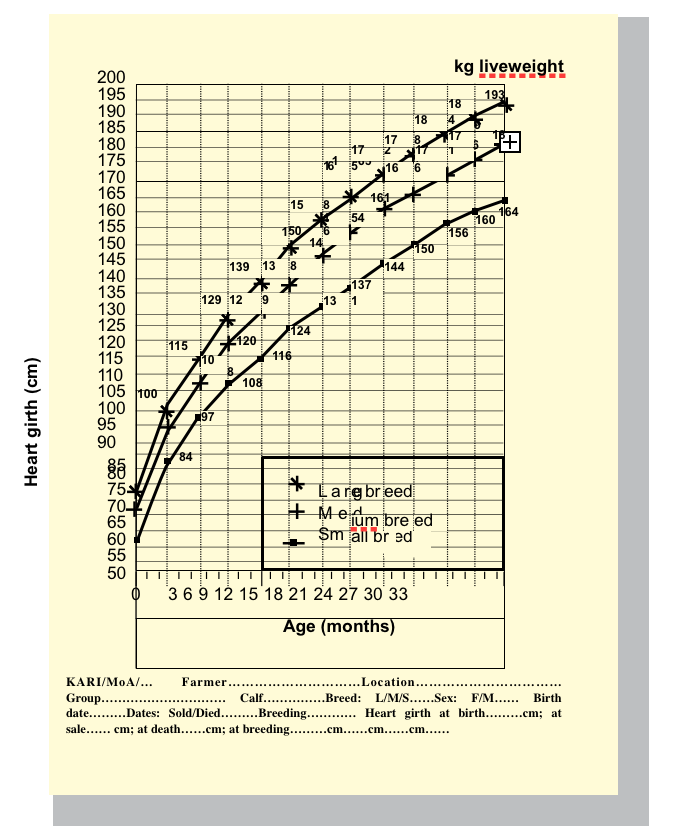

Figure 7.1. Measuring the height of the heifer and estimating the weight based on heart girth (see Appendix 3 Measurements taken are plotted on a chart (Figure 7.2) that shows the expected weight and height at a particular age for a particular breed. If the weight falls below what is expected, the heifer is underweight thus underfed and vice versa. Short heifers indicate low protein in the diet.

Fat, over-conditioned heifers, at the same weight as leaner heifers, are normally younger with less skeletal growth. The pelvic opening is therefore narrow. Due to overfeeding, the calf is normally bigger, leading to dystocia. Underfed heifers will also require assistance and have a higher death rate at calving than normal-sized heifers.

Figure 7.2. Chart of heifer growth.

4. Steaming up

Steaming up refers to providing extra concentrate to a pregnant heifer in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy. This extra concentrate should be fed in the milking parlour if possible, to accustom the heifer to the parlour. This feeding is also intended to allow the rumen bacteria to get accustomed to high levels of concentrate. It provides extra nutrients for the animal and the growing foetus.

Steaming up also allows the heifer to put on extra weight (reserve energy) to promote maximum milk production from the very beginning of the lactation.

Stages of heifer development and expected weight for age

Table 7.1 indicates the tremendous increase in weight during the 9 months of gestation (100–150 kg), which is due to heifer growth and foetal weight. Table 7.2 summarizes the stages in heifer growth and development.

Table 7.1. Expected weight of different breeds of heifer at breeding and calving

| Breed | Breeding | Calving | ||

| Age (months) | Weight (kg) | Age (months) | Weight (kg) | |

| Jersey | 15–16 | 230–275 | 24 | 350–375 |

| Guernsey | 15–16 | 275–300 | 24 | 375–400 |

| Ayrshire | 18 | 300–320 | 27 | 420–450 |

| Friesian | 18 | 300–320 | 27 | 420–450 |

Table 7.2. Expected weight for age at different stages of heifer development

| Stage | Common name | Age (mo.) | Weight (kg) |

| Weaning | weaner | 3–4 | 70–80 |

| Puberty | bulling heifer | 12 | 220–240 |

| Insemination | in-calf heifer | 15–18 | 275–300 |

| First calving | milking heifer | 24–27 | 400–450 |

| Drying | 36 |