Calliandra Production

Credit:National Agroforestry Research Project KARI-KEFRI-ICRAF

Introduction

Calliandra (Calliandra cabthyrsus) is a small leguminous tree that originates from Central America and Mexico. It was introduced in Indonesia to provide shade in coffee plantations, but the tree has now proved more useful for other purposes such as fodder, fuelwood and land reclamation.

In many parts of the world, including Kenya, calliandra cuttings are now used as fodder for grade dairy cows and other livestock. It is particularly appreciated for the protein it can provide when livestock are fed on low-quality roughage or grasses such as napier, which are often deficient in protein.

As an added benefit, calliandra increases the butterfat content of the milk.

In both Kenya and Indonesia, calliandra has been planted on steep eroded slopes to provide stability and prevent soil erosion.

Although calliandra is not pollinated by bees, it is a source for honey. In Indonesia, bees can produce

1000 kg of honey per year from 1 ha of calliandra. A secondary benefit is the improved pollination of coffee trees in the area. The tree also provides good fuelwood that dries well and burns rapidly.

Ecological requirements

Calliandra occurs naturally in some parts of the tropics at altitudes ranging from sea level to 1900 m and where the average annual rainfall is above 1000 mm. It can withstand dry seasons of 2-4 months with less than 50 mm rainfall a month. It can grow on a wide range of soils, including humic Nitosols, humic Andosols and Ferrasols, with a minimum pH of 4.5. But it does not do well on soil that is heavily saturated with aluminium.

It does not tolerate soils with poor drainage that flood regularly. It does not tolerate frost. Calliandra can grow well in Kenya at elevations ranging from coastal lowlands to lower highlands, not exceed- ing 1900 m above sea level.

Establishment

Seed production

Each flower on a calliandra raceme remains receptive for 1 night only, then wilts the following day. The flowers are pollinated at night by bats or hawk moths, which pollinate as they suck the nectar. Only about 1 flower out of 20 produces a pod. Seed production is much less than for other well known fodder species, such as Leucaena spp. and Gliricidia sept- um, but with a bit of effort reasonable amounts of seed can be produced.

Seed orchards should be established with trees that originate from a well-known seed source. You can establish your own orchards but there should be a minimum of 30 flowering trees, either on 1 farm or spread out over several neighbouring farms. This minimum number prevents inbreeding, which has negative effects on seedling quality. Bigger orchards are more successful in attracting bats for pollination, especially in areas where calliandra is newly introduced and bats still have to discover the nectar source. The orchard should be at least 500 m away from other calliandra provenances.

Wide spacing of the trees, such as 3 x 3 m, provides maximum number of flowers and easy access for pollinators. Trees can be coppiced or pollarded to control their size and to make it easier to collect the seed.

Although seed quality is best when the seeds are harvested dry, in practice this is difficult. When pods are very dry they split open explosively, scattering the seeds over several metres. To avoid this, almost-dry pods that have started to turn brown can be picked by hand and dried in a sack. Seeds must be dry to ensure good viability and germination. When stored in an air-tight container and refrigerated at 4 °C, they can remain viable for at least 5 years. When they are exposed to air and kept at room temperature, they will be viable for only a few month. Seeds can also be planted immediately after drying. Seed can be obtained from

- Maseno Agroforestry Research Centre PO Box 25199, Kisumu, Kenya tel: (035) 51163/4

email: icraf-maseno@cgiar.org

- Kenya Forestry Research Institute PO Box 20412, Nairobi, Kenya tel: (0154) 32891/92

- ICRAF, PO Box 30677, Nairobi, Kenya tel: (02) 524000, email: icraf@cgiar.org

- National Agroforestry Research Project, PO Box 27, Embu, tel: (0161) 20116/20873

- Mbale township, PO Box 1402, Maragoli, Kenya, tel: (0331)51454; email:fpagencies@kakamega.africaonline.com

- VI project, PO Box 2006, Kitale, Kenya

Pre-treatment

Calliandra seed has a hard coat that needs to be soft- ened by soaking the seeds in water. We recommend that seeds be soaked in cold water (room temperature) for a minimum of 48 hours. The soaking should be stopped once most of the seeds have swollen, and the seeds should be sown immediately. Seeds should never be boiled, as this kills them.

Calliandra must be inoculated with Rbizobiumbacteria, which can be the same type as for leucaena or gliricidia. The inoculant is first mixed with soil and then with the soaked seeds. Alternatively, calliandra can be inoculated at the seedling stage. The inoculant is mixed in water and poured on the young seedlings.

Another way is to collect soil from beneath an existing calliandra stand and mix it with the nursery soil.

The inoculant can be obtained from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute, PO Box 20412, Nairobi, tel: (0154) 32891/92 or the University of Nairobi, Soil Science Department, PO Box 30197, Nairobi.

Nurseries

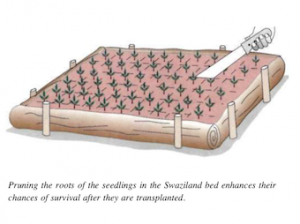

Pruning the roots of the seedlings in the Swaziland bed enhances their chances of survival after they are transplanted

Calliandra calothyrsus seedlings should grow about 3-4 months in the nursery. The raising of the seedlings should be planned so that they are ready to set out in the field at the onset of the rains. The nursery should be located where there is a constant source of water and where the ground is level, with relatively fertile soil and good drainage.

Seedlings can be grown in either polythene bags or Swaziland seedbeds—raised soil beds in which seeds are planted at a relatively wide spacing. The seeds germinate and the plants are allowed to grow in the beds until they are ready for transplanting to the field. Roots are pruned by cutting straight lines in the soil between the seedlings. The bags and the beds are equally effective, but the Swaziland bed method is cheaper.

After the seeds are soaked in water, they are sown directly in the Swaziland beds. If the nursery soil is poor, it should be mixed with compost or old manure, mixing 4 parts of soil with 1 part of compost or manure. The depth of sowing in a Swaziland bed should be 1 cm at a spacing of 10 cm between rows and 5 cm within rows.

Two seeds should be planted per hole and 1 seedling later thinned out if both seeds germinate. After the beds are sown, they should be shaded the same way as for horticultural crops such as sukuma wiki or tomatoes. Plant the seedlings that are thinned out in places where no seeds germinated or plant them in a new row.

The watering regime is twice a day, morning and evening, reduced to a single watering in the last month before field planting. Seedlings should initially be shaded 50% with the shade totally removed in the last month to harden them. The nursery should be weeded as soon as they compete with the seedlings for nutrients, water and light.

In seed orchards, some seeds are likely to fall on the ground and germinate beneath the parent trees. Wildlings produced in this way are also very good for transplanting to the field

Planting

Calliandra seedlings should be planted in the field at the beginning of the rainy season. The bare roots should be kept in water as the planting is done, to prevent the seedlings from drying up. The planting hole should be deep enough to cover the roots. The seedlings can be planted in a line or a block, depending on the land available. Line planting, the most common planting arrangement, creates good hedges. The preferred niches for hedges are external and internal boundaries, around the homestead, along soil conservation structures and under Grevillea robustatrees. Spacing within the hedge should be 0.5 m in either single or double rows. When calliandra is planted in a block, it is best to combine it with napier grass. The planting arrangement is 1 row calliandra to 2 rows napier. Spacing between the rows is 1 m and within rows 0.5 m for both cal- liandra and napier.

Management

First year

After the seedlings have been planted in a well prepared place, a 50-cm area around them should

be kept free of weeds. During the 1st few months, calliandra grows slowly and cannot compete well with weeds. Feed the soil around the trees with well rotted manure or compost.

Calliandra can be coppiced when it has reached a height of 2 m, which is normally 9-12 months after planting. The height on the tree at which the first cutting is made should be low (30 cm) to induce the tree to spread at the base. Later cutting heights can be higher, 0.5-1 m, as the farmer prefers.

Harvest interval

A well-established stand of calliandra can be harvested 4—5 times a year. During the height of the rainy season the cutting interval can be as short as 2 months, but during the dry season regrowth is slower, and the cutting interval may be as long as 4 months. A regrowth of 50—60 cm is a good indication that the tree is ready for the next harvesting.

Cutting height and method

The recommended cutting height is 1 m above the ground. When calliandra is grown between food crops, however, a farmer might want to cut it at a lower height to minimize the shading effect on the crops. Calliandra can be cut successfully even at ground level.

The best way to cut the fodder is with secateurs or pruning scissors, which many farmers in coffee-growing areas have.

This leaves a minimal wound and promotes fast and healthy regrowth. Calliandra can also be grazed, although this increases the mortality of the trees.

Maintenance of soil fertility

When a fodder stand is harvested frequendy and the fodder removed, nutrients are extracted from the soil. These nutrients enter the digestive system of the animal and a large proportion is excreted through manure and urine. To ensure sustainable fodder production, the manure and urine must be returned to the soil where the calliandra is growing.

If the farm is on a slope, zero-grazing units for dairy cows can be constructed in such a way that all slurry is collected in a pit from which it can flow by gravity to foder plots situated lower down the slope.

When calliandra has nodulated, it can supply its own nitrogen requirement. Although symbiosis with mycorrhiza fungus helps to absorb phosphorus, this element is likely to be the first that becomes deficient in the soil when no manure or urine is returned.

Dry season feeding

Calliandra can be cut late in the rainy season and conserved for dry season use. The foliage should be dried gently (under shade rather than in full sun if possible) on a suitable surface (e.g. sackcloth) so that leaflets that fall off are not lost. Alternatively, the foliage can be left uncut on the tree and harvested when it is needed. For optimum fodder availability, the trees should be pruned 6 months before they are needed for the dry season. At that pruning, a considerable amount of fuelwood can be harvested as well.

Calliandra used as a live stake for passion fruit in Uganda.

Diseases

Calliandra is relatively free of diseases and pests. However, some of the following might occur.

Root rot {Armillaria mellea) — This fungus affects roots in high-altitude areas from which forest has recently been cleared. If the fungus is present in roots of other tree species and those roots touch the calliandra roots, they get infected as well. The rot results in the death of the tree. Removal of old tree stumps and their roots minimizes the occurrence of this disease.

Scales — These insects attach to the stem and can kill the tree. Some scales appear white and powdery, others are smooth. The stem sometimes turns black. Scales are easily treated by spraying the affected areas with a washing detergent dissolved in water.

Rust {Ravenelia spp.) — These fungi usually appear on the underside of leaves, where they look powdery and occur as small raised dots.

Pink disease (Corticium salmonicolor) — This disease is associated with intense coppicing.

Die back {Nectria ochroleucd) — This fungus occurs in association with other fungal attacks. It causes general blight (discoloration of leaves) and sometimes cankers (swollen or sunken lesion in the wood).

Viral or bacterial diseases have not been recorded on calliandra. Chemical control for pests and diseases is not recommended because of the negative effect residuals have on animals and the environment.

Feeding calliandra to dairy cattle

Nutritive value

The edible fraction of calliandra has a crude protein (CP) level of 20-25% of the dry matter, depending on the cutting interval and the leaf-to-stem ratio of the offered material. This CP content is much higher than that of napier grass (average 8.5%). Calliandra can be mixed with napier in such a way that the CP content of the diet reaches the required 13% for dairy cows.

Cows will usually eat stems up to a diameter of 1 cm when the stems are succulent or 4 mm during the dry season when they are more lignified. Digestibility of fodder in general is determined by factors such as fibre content and certain types of tannins. Fibre of calliandra is comparable with that of other tree fodders (acid detergent fibre 22—31%, neutral detergent fibre 45-50%).

However, calliandra has a high concentration of condensed tannins. These tannins bind with the organic matter and consequently prevent the absorption of the material in the digestive tract. The digestibility of calliandra ranges between 40% and 60%. High-quality fodder supplements normally have a digestibility of more than 65%.

Rations

For the farmer to obtain high economic returns, lactating cows with high milk producing potential are normally fed protein rich supplements like tree fodder. Calliandra is used as a protein supplement; the basic diet normally consists of napier or other grass, weeds, crop residues (banana stems and leaves, maize stover, sweet potato vines), hay or straw.

On station and on farm experiments with dairy cows have shown that it is possible for about 3 kg of fresh calliandra fodder (1 kg dry matter) to replace 1 kg of dairy meal without affecting milk production. In this research, an additional 3 kg of fresh calliandra increased milk production by 0.6 kg, the same increment that is obtained from an additional 1 kg of dairy meal. This would mean that 6 kg of fresh calliandra could replace 2 kg of dairy meal, when the farmer does not have money to buy the dairy meal. In practice, however, this substitution rate is not an absolute, but will vary considerably according to such factors as basal feed composition and animal health. The ratio can be viewed as a starting point for farmers experimenting with the feeding of calliandra, but the actual ratio on their farms may be very different.

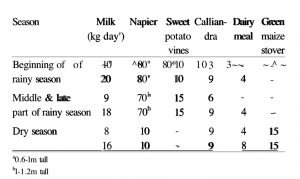

Table 1 shows example rations for large dairy cows, for 2 production levels, during the beginning of the rainy season, the middle and late part of the rainy season, and the dry season. When calliandra is in abundance, it can be fed to young stock, bulls and non-lactating cows as well.

Freshness

It used to be thought that even a few hours of wilting would drastically reduce the quality of calliandra fodder. Recent experiments with sheep have shown, however, that drying calliandra can actually increase voluntary intake. Even though drying causes a small reduction in quality, the effects on intake and quality can cancel each other out giving no overall effect on animal production. Where voluntary intake of fresh calliandra is very high, as for dairy cows in central Kenya, the best results may be achieved with fresh leaves. But in situations where leaves cannot be fed immediately after harvesting, such as some cut-and- carry systems, wilted leaves can also be fed with good results. It is also possible to conserve leaves for dry season use.

Calliandra for other livestock

Calliandra can be fed to dairy cattle, local cattle, goats, sheep, rabbits and poultry. Basal diets are similar as for dairy cows (see above). The amount of calliandra fed is normally 1/4 to 1/3 of the total diet. Rabbits are best fed on a mixture of weeds, grains and tubers (not fresh cassava), with 1/3 of the diet consisting of calliandra. Feeding on calliandra alone causes weight loss. Poultry can be supplemented with dried calliandra although this tends to increase feed intake and reduce egg production. The exact reasons for this are not known. A little bit of dried calliandra mixed with layers mash (a small handful to 1 kg of layers mash) improves the colour of the yolks without affecting egg production. It is anticipated that calliandra is not very digestible for pigs, although this has never been tested.

How much calliandra is needed?

The amount of fodder that calliandra can pro- duce depends on factors including climate, soil fertility status and altitude. Productivity of calliandra is often expressed in kilograms of dry matter per metre of hedge per year. It can safely be assumed, for a wide range of conditions, that calliandra produces 3 kg DM (dry matter) per metre of single hedge per year. If a farmer wants to feed 1 cow 6 kg fresh calliandra (2 kg DM) every day in a year, the farmer would need a hedge approximately 250 m long. If the spacing between the trees is 50 cm, the total number of trees required would be about 500.

There are several other benefits of calliandra:

- it increases the butterfat content of milk and therefore its ‘creaminess’.

- if used as a supplement, it may improve the cow’s health and shorten the calving interval

- it provides firewood, fencing, boundary marking,

- erosion control,

- and ornamental values

Slightly negative impact that a calliandra hedge has on adjacent crops

- by shading them or interfering with their roots.

- It is also important to realise that calliandra will sometimes need to be fed at a higher level to substitute for the same amount of dairy meal, and this will reduce its profitability.

Opportunities and limitations

Opportunities

- Calliandra is palatable to a wide range of livestock species.

- The tree grows vigorously and coppices well.

- The trees can be planted in many different niches on farm.

- Calliandra leaves can be fed dry or fresh.

- Calliandra can replace or supplement dairy meal. Both options increase profitability.

- The tree supplies its own nitrogen require- ment by fixing it from the air.

- Calliandra is relatively free of diseases.

- Secondary benefits are erosion control when the trees are planted on the contour and fuel wood.

• The tree does not produce many seeds.

• It can suppress the yield of adjacent crops.

Limitations

- Digestibility of calliandra is lower than that of other well-known tree fodders

- The tree does not produce many seeds.

- It can suppress the yield of adjacent crops.

Ongoing research

- On-farm calliandra nurseries

- Long-term effects of feeding calliandra

- Anti-nutritive factors in calliandra

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank those people working at research institutes, extension services and farming communities who requested that this bulletin be written. The input of IN Thendiu in the 1st consultative meeting on the bulletin content is gratefully acknowledged. After a series of drafts, a 2nd consultative meeting was convened to deliberate further on technical details and format. A number of people in the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Marketing and NGOs attended this meeting and made useful contributions: Maina Kiondo, Kiama Augustus, Elizabeth Kang’ara, Jeremiah Matemu and Cornelius Kasisi. The work that led to this publication was supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), under the Forestry Research and Livestock Production Programmes, as well as the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada, through a technology transfer grant. Janet Stewart, Oxford Forestry Institute, UK, provided useful com- ments for updating this bulletin. And finally, we appreciate the significant contributions of Hellen Arimi and Mick O’Neill to these projects.

The production of the second edition of this publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Project R6549, Forestry Research Programme.